House rules

House rule #2:

Evidence is unambiguous

“Here the question that is seldom asked is: ‘whose outcomes count?’” (p. 673)

RCTs assume that the evidence from a trial is incontrovertible and not open to interpretation.

Tibetan and western doctors center different data and create different evidence when looking at the effectiveness of a treatment.

When there is disagreement between paradigms about whether a treatment “worked” or not, the House (Western medical practice) determines who is right.

House rules

House rule #3:

Isolation of active ingredients

[I]t is generally assumed that reliable remedies can be reduced to a few basic active ingredients that can be evaluated singularly for their effectiveness.” (p. 673)

RCTs like those required by the NCCAM are often incompatible with the treatments in Tibetan medicine, which might include many carefully prepared ingredients.

Western science is deeply invested in the idea that physiological processes like disease and the compounds that affect / alleviate them are discrete and can be isolated.

Next class

Science, race, and health

- Poudrier (2007)

The Geneticization of Aboriginal

Diabetes and Obesity

A note on terminology

In contemporary discourse within the Canadian context, the term “Aboriginal” is used mainly in specific legal contexts. When referring to First Nations, Inuit, and Métis peoples of this continent as a group, and particularly when contrasting with settlers and colonial populations, the term “Indigenous” is usually preferred.

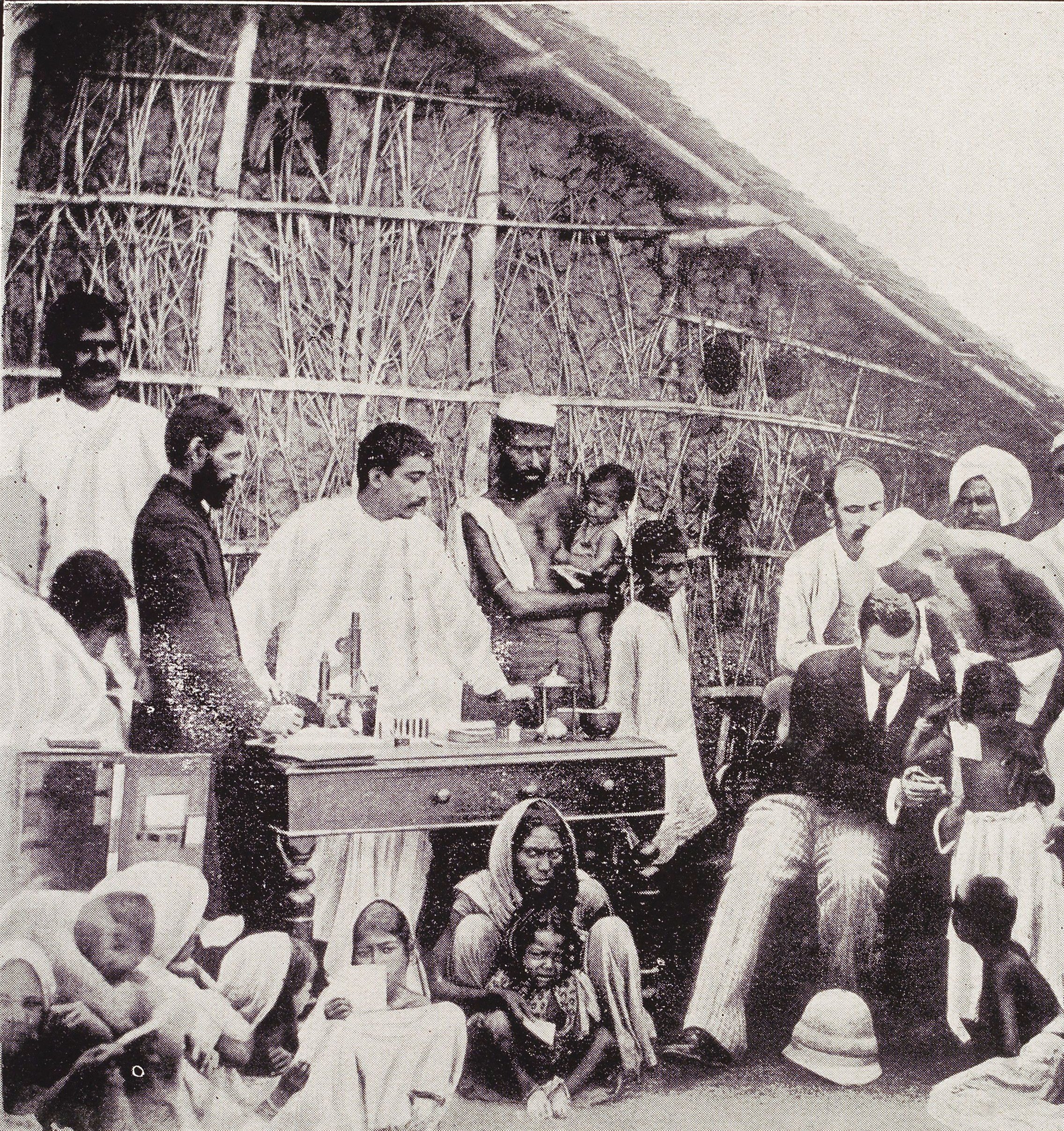

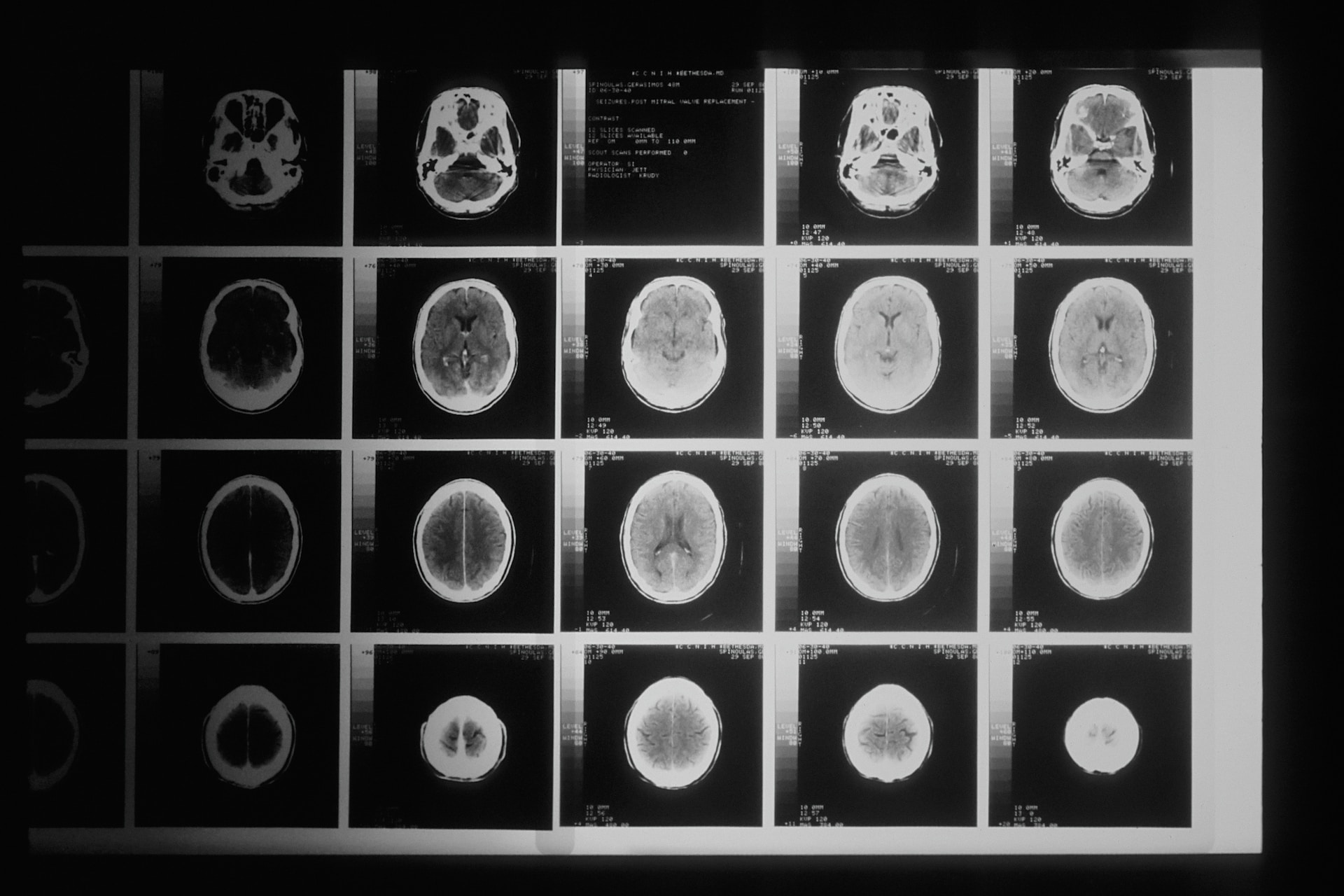

Image credit

Photo by Waldemar Mordecai Wolffe (via Wellcome Collective)

Photo by National Cancer Institute on Unsplash

Photo by Muneer ahmed ok on Unsplash

Photo by pina messina on Unsplash