Next class

Next class

Required reading

- Wolfe (2018)

Introduction to

Freedom's laboratory: the Cold War struggle for the soul of science

Image credit

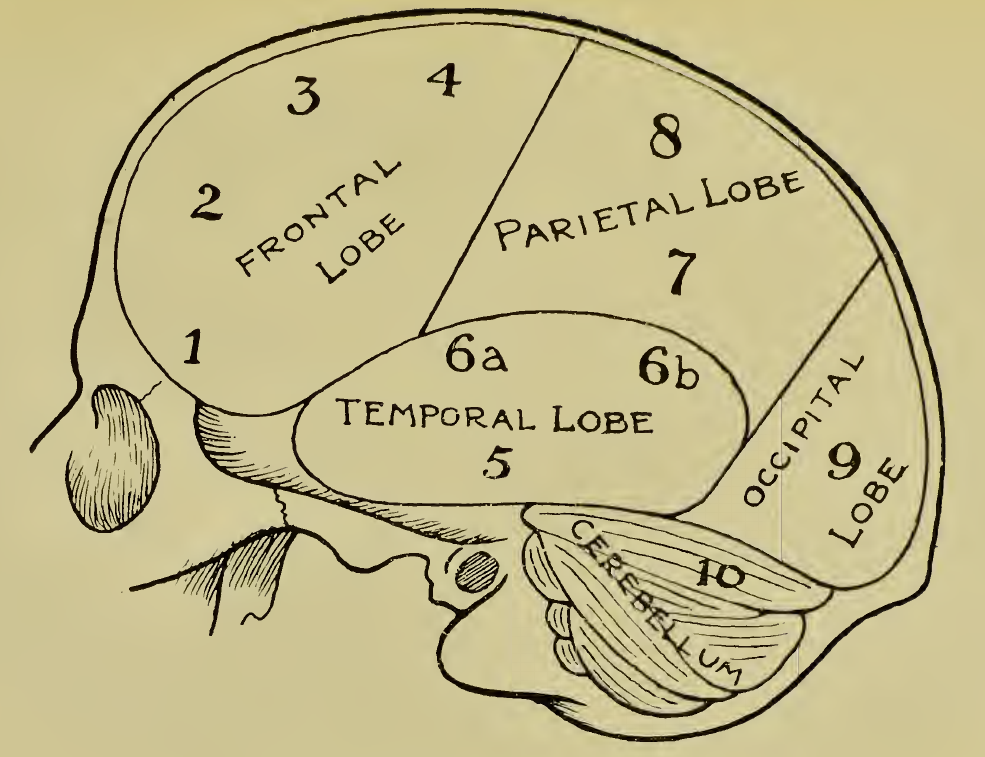

Plate 35 from Hollander (1902), Scientific Phrenology via archive.org

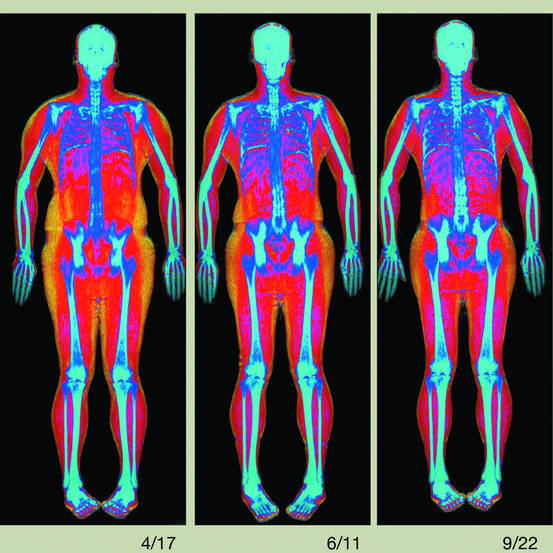

Image by Hologic Inc, via The Wall Street Journal

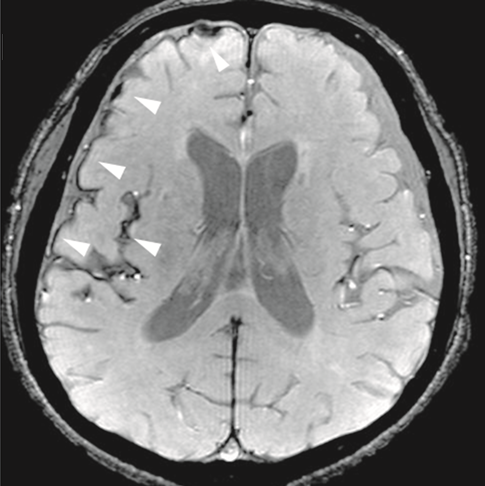

MRI from Hongwei et al. (2015)

Print from Plants of the coast of Coromandel

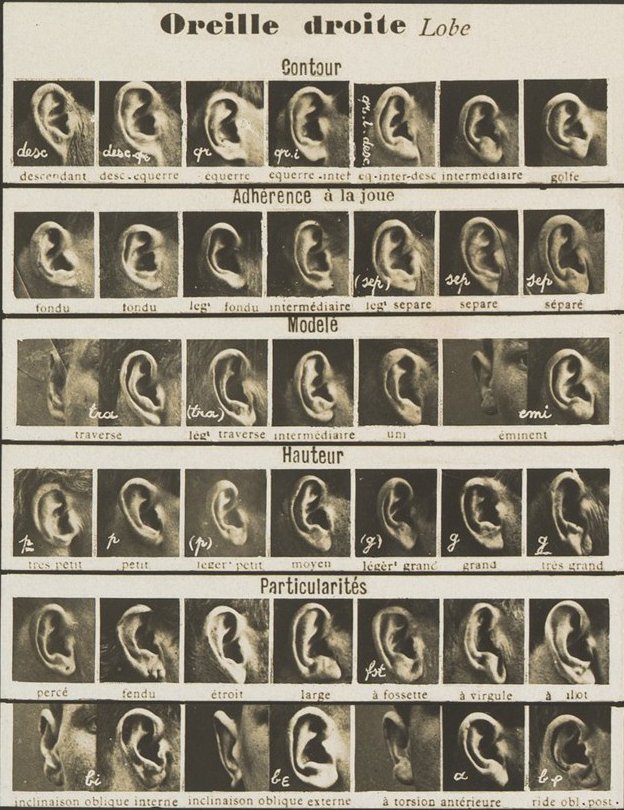

Photos by Alphonse Bertillon, via The Metropolitan Museum

Photo by Michael Dorausch via planetc1.com

Page 1 of 12